European Cultures Became Familiar With Islamic Art Through

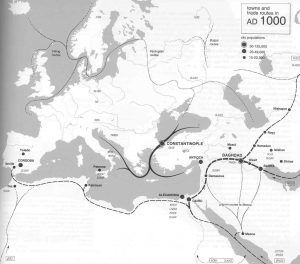

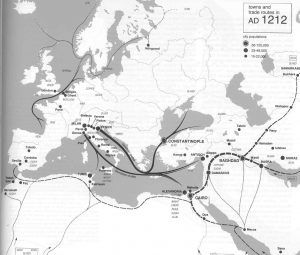

Merchandise in much of Europe declined afterward the fall of Rome, and towns and cities declined in size, roads were not safe, and feudal manors were an important and self-sufficient unit. Urban life remained active in the e, where cities grew specially with the ascent of Islam, when Muslim societies—though not unified in a unmarried empire—spread from the borders of China to the Iberian Peninsula in Europe on the Atlantic and Mediterranean.

The Crusades did not marker the beginning of trade between Muslim and Christian lands in Europe. Italian merchants traded across the Mediterranean with Constantinople, Syrian arab republic and Egypt, and Spanish Muslims and Christians traded actively and produced fine goods for sale. Sicily, under Muslim rule and so nether Norman dominion, was a source of contact and production of goods. Amongst the most precious manufactures of trade were metal wares, silk textiles, and glass, besides as some food stuffs, dyes and perfumes.

The contribution of the Crusades was that trade increased as Europeans traveled and became more familiar with exotic goods. Increased contact and trade was part of the reason for the ascent of towns and cities in western Europe, starting in Italia.

Despite warfare during the long period of the Crusades, Italian merchant cities like Amalfi, Genoa, Venice and Florence strengthened trade ties with ports in the Levant (eastern Mediterranean coast), where they centrolineal with crusader states to gain access to ports such every bit Latakia, Tripoli, Acre, Alexandria, and Damietta. As merchandise increased with demand and production in northern Europe, trade routes on the Atlantic and the North Body of water joined with Mediterranean routes, and carried trade appurtenances in to Europe past river trade and across the Alps.

Trade and travel meant people saw, heard, tasted and touched new things, and influences in the arts and lifestyles moved with them, bringing new styles of building, decoration, clothing, cooking and music—for those wealthy enough to afford the new things. In the following sections, read almost some objects of fine living that entered Europe in part every bit an outcome of the exchanges during the Crusades.

Map source: http://academic.udayton.edu/williamschuerman/Trade_Routes.jpg

Spanish Muslim Traveler Ibn Jubayr Speaks about Armies and Caravans in the 12th Century

From Muhammad ibn Ahmad Ibn Jubayr, (Roland Broadhurst, translator), Travels of Ibn Jubayr: Being the Chronicles of a Medieval Spanish Moor Concerning His Journey to the Egypt of Saladin, the Holy Cities of Arabia, Baghdad the City of the Caliphs, the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, and the Norman Kingdom of Sicily (London: Cape, 1952), pp. 300–301.

Introduction

Ibn Jubayr (b. 1145) was a resident of al-Andalus, or Muslim Spain, during the 12th century. His journey was the result of an unfortunate incident at the courtroom of his ruler. It seems that the ruler forced the pious scholar Ibn Jubayr to taste an alcoholic beverage in jest. Ibn Jubayr was and so disturbed that it acquired the ruler to regret his actions. To make up for the outrage, he is said to have given Ibn Jubayr a quantity of gold. To absolve for his sin of weakness, Ibn Jubayr vowed to use the money for a Hajj, or pilgrimage journey to Makkah. He did so, and made a tour of several other places around the Mediterranean. Historically, his travel account is especially interesting since he traveled during the Crusades, at the fourth dimension of Salah al-Din (Saladin). He was an excellent observer of his time.

From Ibn Jubayr's Travels in Egypt, Palestine, and Syrian arab republic:

I of the astonishing things that is talked of is that though the fires of discord burn between the two parties, Muslim and Christian, two armies of them may run across and dispose themselves in battle array, and yet Muslim and Christian travelers volition come and go between them without interference. In this connection nosotros saw at this time, that is the month of Jumada al-Ula [in the Islamic agenda], the departure of Saladin with all the Muslims troops to lay siege to the fortress of Kerak, one of the greatest of the Christian strongholds lying astride the Hejaz road [the pilgrimage route to Makkah] and hindering the overland passage of the Muslims. Between it and Jerusalem lies a mean solar day's journey or a footling more than. It occupies the choicest part of the land of Palestine, and has a very wide rule with continuous settlements, it existence said that the number of villages reaches 4 hundred. This Sultan invested information technology, and put it to sore straits, and long the siege lasted, but still the caravans passed successively from Egypt to Damascus, going through the lands of the Franks without impediment from them. In the same fashion the Muslims continuously journeyed from Damascus to Acre (through Frankish territory), and likewise not one of the Christian merchants was stopped or hindered (in Muslim territories).

The Christians impose a taxation on the Muslims in their country which gives them full security; and likewise the Christian merchants pay a tax upon their goods in Muslim lands. Agreement exists between them, and there is equal treatment in all cases. The soldiers appoint themselves in their war, while the people are at peace and the world goes to him who conquers. (Ibn Jubayr, born 1145) (Commendation: pages 300–301)

Metalwork

Ayyubid Canteen with Christian and Islamic Motifs

The Freer Canteen is one of the finest examples of Islamic metalwork from the eastern Mediterranean. It is made of brass inlaid with silver and a blackness substance called niello to highlight the design. It is large, nigh 37 cm (ane foot) in diameter. The design is based on units of 3 bands, circles, and scenes. At the middle on the domed top is the Madonna and Christ Kid enthroned with angels holding up the throne above and below, attended by 2 men praying, i with a turban and the other a halo. Three looped circles contain animals, fish, and birds, and between them are scenes from Jesus' life: his birth or nascence scene, presenting him in the temple, and Christ'south entry into Jerusalem.

On the shoulder of the bottle are bands with an inscription in Arabic, with a approving wishing the owner glory, security, prosperity and good fortune, as well as victory and enduring power, "everlasting favor and perfect honor." The eye band is an blithe inscription formed by a procession of real and fantastic creatures, human horsemen and camels whose bodies brand up the strokes of the Arabic letters. This extremely intricate inscription reads: "Eternal celebrity and perfect prosperity, increasing good luck, the chief, the commander, the almost illustrious, the honest, the sublime, the pious, the leader, the soldier, the warrior of the frontiers." (Atil, p. 124) The lowest band is a serial of thirty roundels with a hawk attacking a bird, and seated figures of musicians and figures drinking, and bowls of fruit. The bottom of the bottle has twenty-five standing figures divided by pillars. They represent saints in robes with books, censers and others show soldiers with weapons. One ready may show Mary and the Affections Gabriel. The central ring on the bottom shows a scene of knights in a tournament. Even the neck of the canteen has intricate inlaid inscriptions and designs.

The patron who commissioned this remarkable piece from a Syrian or Iraqi artisan was a Christian familiar with knightly endeavors—peradventure a Crusader. The canteen is one of the most spectacular examples of this kind of Islamic metalwork.

Image credit: Bottle, Ayyubid catamenia, mid-13th century, Mosul School, http://www.asia.si.edu/collections/edan/object.php?q=fsg_F1941.10.

Contumely, silver inlay, DIMENSION(S) H x West (overall): 45.2 ten 36.vii cm (17 13/16 x 14 vii/16 in), Syrian arab republic or Northern Iraq, Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, Freer Gallery of Fine art, ACCESSION NUMBER F1941.10

Source for text: Esin Atil, W. T. Chase, Paul Jett, Islamic Metalwork in the Freer Gallery of Art (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Freer Gallery of Art, 1985), pp. 125–33 (canteen); pp. 137–43 (Basin).

Ayyubid Basin with Christian and Islamic Motifs

This example of inlaid brass and silver Islamic metalwork was created during the reign of Sultan al-Malik al-Salih Najmuddin Ayyub. He was the son of al-Malik al-Kamil and the last Ayyubid ruler, who reigned from 1240–1249. It was commissioned for the Sultan, according to inscriptions on the interior and exterior of the bowl. The basin is decorated with both Islamic and Christian themes, and so information technology might take been commissioned either by a wealthy Muslim or Christian patron, to demonstrate religious tolerance in Ayyubid Syria during that time, standing the legacy of the Sultan'due south father, al-Kamil.

On the outside of the large bowl (50 cm/20 inches in diameter) are scenes from Jesus' life: the Annunciation, the Virgin and Child enthroned, the miracle of raising Lazarus from the dead, Christ's entry into Jerusalem, and a scene that might represent Christ'south Last Supper with his disciples. Other designs on the outside of the bowl evidence a polo game and a procession of realistic and imaginary animals. Between them are seated musicians in round medallions. Inside the basin, a row of thirty-nine standing figures separated past pillars and arches represent saints or other important persons. The inscription around the inside rim celebrates the ruler Najm al-Din Ayyub as "Our chief, the illustrious, the learned, the efficient, the defender, the warrior, the supported, the conquistador, the victor, lord of Islam and the Muslims…may his victory be glorious." Whether commissioned by a Muslim or Christian patron for the Sultan, the combination implies religious tolerance in thirteenth-century Ayyubid Syrian arab republic. Najm al-Din lost his life in Egypt in 1249 while fighting against the Crusade of St. Louis.

Image Credit : Basin, Ayyubid period, Reign of Sultan Najmal-Din Ayyub, 1247–1249, http://www.asia.si.edu/collections/edan/object.php?q=fsg_F1955.10

Brass, inlaid with silver, DIMENSION(South) H ten West ten D: 22.v ten 50 x 50 cm (8 seven/8 x 19 11/16 x 19 11/16 in), Syria, Probably Damascus, Freer Gallery of Art, Accretion NUMBER F1955.x Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment

Source for text: Esin Atil, W. T. Hunt, Paul Jett, Islamic Metalwork in the Freer Gallery of Art (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Freer Gallery of Art, 1985), pp. 125–33 (bottle); pp. 137–43 (Basin).

Silk Textiles

The secrets of silk cultivation and weaving circuitous patterns called brocades belonged first to China. Silk weaving spread along the Silk Roads to Byzantine and Sassanian Western farsi purple workshops before the ascent of Islam, and was adopted past the Muslim Abbasid caliphs, who established their own caliphal workshops. Such royal fabrics were possessed only by the most aristocracy of rulers and courtiers. Their designs reflected symbols of the ruler in the shape of mythic animals, and Muslim caliphs often wove Arabic inscriptions of blessings and of their names. They were given as gifts of robes of honor to show majestic favor. Information technology was the ultimate in "power dressing" to be able to wear such a garment.

The engineering science of silk cultivation, dyeing, and complicated brocade looms spread beyond the Mediterranean with Islam, carried to Egypt and across North Africa, Spain, and Sicily. Brocade workshops expanded beyond the courtly product and began to produce fine textiles for export. Medieval churches and nobles imported brocades from Spain, Sicily, and Fatimid Egypt for wall hangings, church decoration and vestments (priestly garments worn while celebrating mass). When Sicily fell to the Normans, they inherited silk production centers. As other centers in Italy began to produce silk brocades, they copied the techniques and patterns so well that information technology is difficult to tell their origin, but imports also continued from the East.

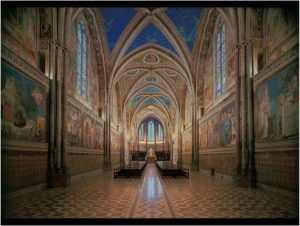

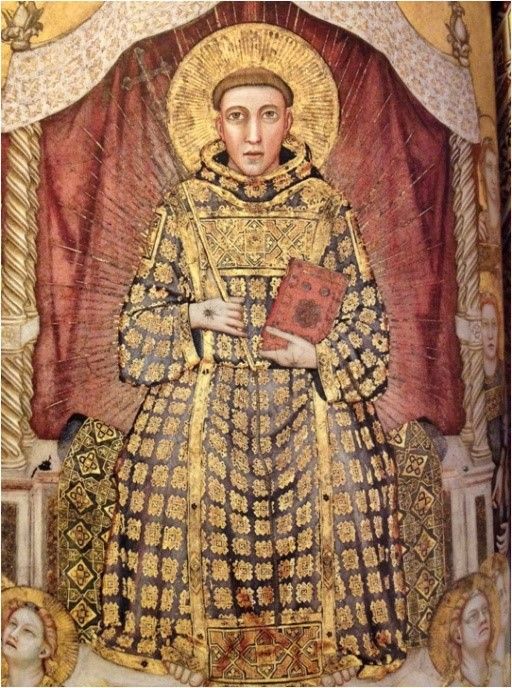

Nosotros know what uses these brocades served from paintings made subsequently the thirteenth century in Italy, and later in Spain. Giotto's Lives of St. Francis in the basilica at Assisi were the primeval Italian paintings showing imported Islamic silk brocades. The prototype here shows Saint Francis Appears to Pope Gregory IX in a Dream, painted betwixt 1296 and 1305, in the Basilica of St. Francis at Assisi, Italia. A wall hanging behind the pope has intricate geometric designs in bright silk, and a band that imitates Arabic script, which in the original would accept had a approving or other repeated phrase for the owner. Some other hanging is a awning over the bed, and these rich cloths cover the bed and a bench in forepart of it. The fabrics are probably Castilian imports. In Syria and Egypt, animal patterns were common, which were often copied in early Italian brocade workshops. Even sacred paintings of the Madonna and Child showed the Virgin Mary clothed in fabrics with Islamic designs and Arabic script.

This illustrates that the beauty and luxury of the fabrics was more important than any religious references. These fabrics are besides an important sign of trade across the Mediterranean, which only increased as more products from the Due east became known in Europe.

Image credit: Giotto di Bondone (d. 1337), Dream of Pope Gregory Nine, from the fresco series of the Legend of St. Francis in the Upper Church, Basilica of San Francesco, Assisi; Date: before 1337, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Saint_Francis_cycle_in_the_Upper_Church_of_San_Francesco_at_Assisi.

Source for text: Rosemond Mack, From Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300–1600 (Berkeley: Academy of California Press, 2002), pp. 27–22; Alavi and Douglass, Emergence of Renaissance: Cultural Interactions betwixt Europeans and Muslims (Fountain Valley, CA: Quango on Islamic Education, 1999), pp. 263–74.

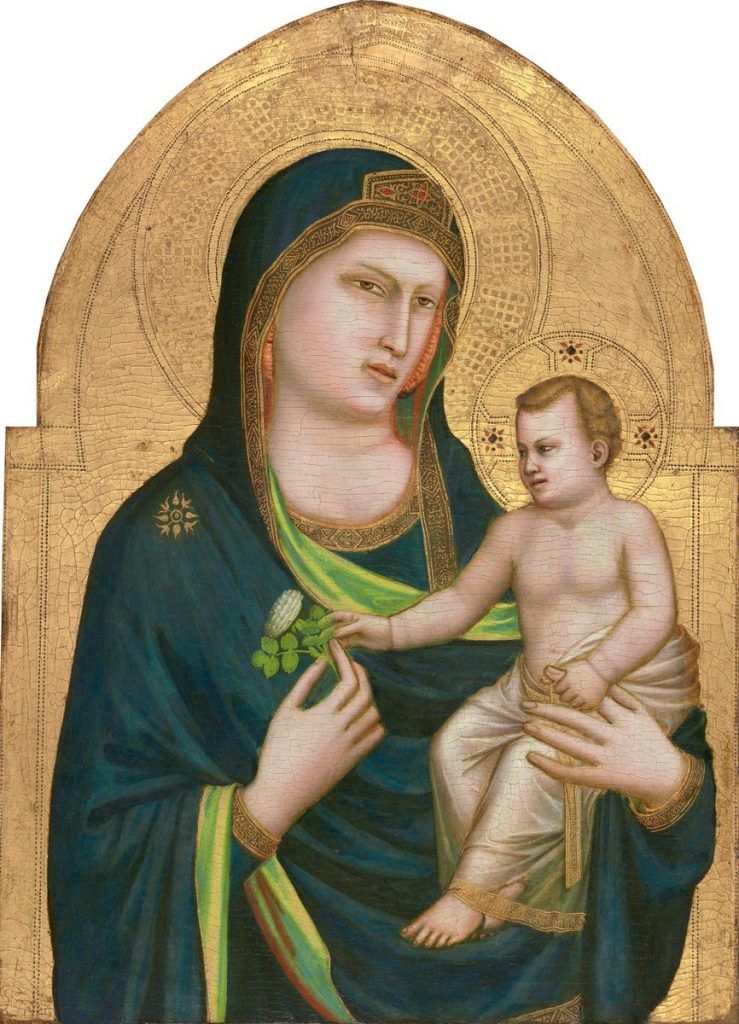

Madonna and Child

This painting of the Madonna and Child shows the Virgin Mary against a gilded background with a halo, in gilt. Italian artist Giotto (ca. 1266 – 1337), has clothed her in a silken veil and robe with bands of embroidery called tiraz, with Arabic lettering. Such fine veils which covered nigh of the trunk were typical for wealthy Muslim women of the courts. The Christ child is also wrapped in a fine fabric with embroidered bands. The painter has created an paradigm of the nearly cardinal figures in Christianity for a setting where worship took place, using a typical Islamic luxury fabric and mode of dress for Muslim women. The embroidery bands in Giotto's painting are not legible, just such tiraz bands had blessings in Arabic from the Qur'an, alternating with geometric designs. The fabric was used to create an image of nifty beauty using the about rare and expensive fabrics of the fourth dimension, which were imported from Due north Africa or the Levant.

This painting is merely one of many examples of Madonna and Child paintings, some of which show halos modeled on fine Islamic metalwork, with Standard arabic script engraved effectually the circles. In this example, the halos contain geometric designs in gilded, only the entrance around the painting shows faint imitations of Arabic lettering. The ports and cities that exported these goods from the East were contested between Christian and Muslim armies, merely the fabrics and other luxury items were not controversial fifty-fifty in sacred art, just precious and desirable.

Epitome source: Giotto, Italian (ca. 1266 – 1337), Madonna and Child, painted ca. 1320/1330, tempera on pane Dimensions: 85.5 10 62 cm (33 xi/16 ten 24 7/16 in.) framed: 128.3 x 72.1 x 5.1 cm (50 1/2 x 28 3/viii x 2 in.), National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Accession No.1939.1.256, https://images.nga.gov/?service=nugget&action=show_zoom_window_popup&language=en&nugget=20008&location=grid&asset_list=20008&basket_item_id=undefined. (expand image to testify detail online)

Glassware

About 1260

This chalice was fabricated as part of a fix made in Syria during the Crusader period, about 1260. There are two of import features of the chalice. First, its drinking glass is almost colorless, which required the addition of sure chemicals. 2nd, it features colored and gold enamel designs that were practical and then heated again to fuse them to the drinking glass. Both techniques were adopted by Venetian glassmakers on the famous island of Murano where glass artisans and their secrets were kept. Another feature of this chalice is that Islamic imagery and Standard arabic script were combined with an important Christian decorative theme—an image of Jesus entering Jerusalem riding on a gray donkey.

Image source: Syria, ca. 1260 (Crusade, glass with gilding and enamel), Walters Art Museum, Accession Number 47.18, http://art.thewalters.org/particular/30828/beaker-2/.

The Crusades and Glassmaking Applied science

In their book Islamic Engineering, Donald Hill and Ahmed al-Hassan cite the text of a treaty between Bohemond VII, prince of the Syrian city of Antioch, and the Doge (ruler) of the Italian city-state of Venice:

a treaty for the transfer of technology was drawn up in June A.D. 1277. . . . It was through this treaty that the secrets of Syrian glassmaking were brought to Venice, everything necessary beingness imported directly from Syria—raw materials besides equally the expertise of Syrian-Arab craftsmen. Once it had learnt them, Venice guarded the secrets of technology with great intendance, monopolizing European glass manufacture until the techniques became known in seventeenth century France.

Text Source: Ahmed al-Hassan and Donald Hill, Islamic Technology (New York: Cambridge University Press/UNESCO, 1987), p. 153.

Rosamond Mack, in her book From Boutique to Piazza, describes the Venetian island of Murano where glass-making was isolated both for its fire take chances, simply besides to protect its secrets. Mack acknowledges the influence on Venetian glass of Islamic and Byzantine techniques and decorative styles. Before the Crusades, Venetian artisans made glass. During the Crusades, their industry benefitted from trade relations and transfers of material. They imported brine, an essential ingredient, "through its merchant colonies in the crusader states. A treaty of 1277 between Doge Giacomo Contarini and Bohemond VII, prince of Antioch, mentions duties on broken drinking glass loaded at Tripoli that served as raw material in Venice. Production and markets were varied past the end of the Crusades; "water bottles and odour flasks and other such graceful objects of drinking glass" were proudly borne in the countdown procession for Doge Lorenzo Tiepolo in 1268, the Polo brothers opened the Oriental market for Venetian glass beyond the Alps."

Text Source: Rosamond Mack, From Boutique to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300–1600 [Berkeley: University of California Printing, 2002], p. 113.)

For more on Islamic glass technology and its history, see "Glass" at http://islamicspain.tv/Arts-and-Science/The-Civilization-of-Al-Andalus/index.html.

Islamic Artistic Influences in the Basilica of San Francesco

St. Francis's visit to the courtroom of al-Malik al-Kamil during the 5th Crusade at Damietta, on the Mediterranean coast of Arab republic of egypt has meant different things in different eras. Chroniclers of the Crusades, Church biographers of Francis after he was fabricated a saint ranged from his want to convert the Sultan, to seek martyrdom, to bear witness that Christianity was the True Organized religion, and the uncomplicated desire in emulation of Jesus, to end warfare and bring peace. In the 21st century, the Crusades have come to correspond a seemingly unbridgeable split up between East and West, Islam and Christianity, even though historians accept discovered a parallel history of peaceful exchange during the aforementioned period, and afterward.

After St. Francis's death, the simple man whose life was a symbol of richness of spirit and material poverty very apace became a canonized saint. On 16 July 1228, Francis was canonized by Pope Gregory IX in Assisi, and he laid the foundation rock of the new church the following day. The pope arranged to build a worthy tomb and basilica, site of pilgrimage, and a convent as abode for the Friars Minor, the Lodge of the Franciscans. It was designed by Maestro Jacopo Tedesco, the most famous architect of his time in Italian republic, and supervised by Blood brother Elias, one of St. Francis'due south first followers. It was built between 1230 and 1253, with a Lower Church and an Upper Church, and a catacomb in which St. Francis is buried. It became a UNESCO globe heritage site in 2000.

Rev. Michael Calabria, scholar of Islamic fine art, and a Franciscan himself, has studied the Basilica's architectures and decorations. The Basilica of St. Francis shows many signs of artistic influences from Muslim earth that are seldom noticed by historians of Italian early Renaissance art, and may accept been conscious or unconscious influences. The Basilica is known as the get-go Italian Gothic edifice, and its Romanesque and Byzantine elements are likewise noticed, peculiarly in the burial crypt. It is really virtually similar to buildings called Italo-Islamic, which are found in southern Italy in places influenced by Sicily'south Islamic past and the Norman-Islamic forms that followed. These influences in Italy were the result of merchandise networks between maritime Italian urban center-states such every bit Venice, Amalfi, and Genoa. Inland Assisi was not role of these networks, but it was located lxx miles from the port city of Ancona, so the merchants and nobles of Assisi were exposed to those networks and the goods and ideas that came through them.

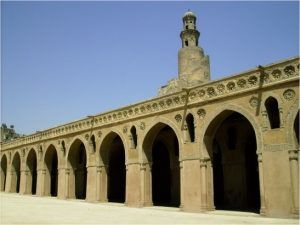

The first sign of Islamic influence is the use of pointed arches, which are a signature of European gothic architecture. Pointed arches allow wider arches in walls, making room for windows—specially stained glass windows every bit seen in the image of the interior of the upper church. Pointed arches are found in many Islamic buildings, appearing outset at 9th century Samara in Iraq, according to Michael Calabria.

Crusaders and travelers would have seen many of these buildings in Palermo, Sicily, in Spain, in the Levant, and in Egypt, such as the Mosque of Ibn Tulun in Cairo, which dates to the 9th century.

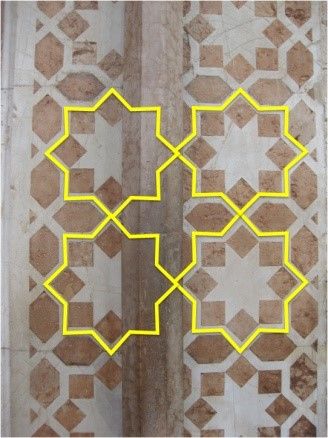

The adjacent element of Islamic influence is found throughout the Basilica and its frescoes and ornamental features. It is the eight-pointed star. The 8-pointed star originated in the aboriginal Near Eastward, in textiles. In Coptic tradition, the number 8 represents renewal & rebirth, the story of Noah's eight people surviving the overflowing, and Christ rising on the eighth, not the 7th solar day. In Islamic tradition, the throne of God is supported past 8 pillars, with 8 angels conveying the throne of God, and eight gates to 8 Paradises after the Judgment Day. In the Qur'an, the word "Kun!" or "Exist!" is mentioned viii times—the Discussion used past God to bring creation into existence—how Adam and Jesus were created.

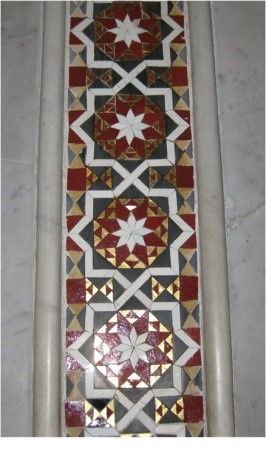

The eight-pointed star appears in many places in the Basilica: on the entrance to the Lower Church, decorating the arches, and every bit mosaics on the floors. In the nave, 8-pointed stars, with internal 8-point star, and connected by rectangular & triangular forms with interlaced lines. A variation of the pattern that appears in the basilica is modeled on another Islamic geometric design—the tessellated star and cross pattern—equally in these turquoise ceramic tiles from Kashan.

The star and cross design appears also in the textiles and architectural featuers depicted in the frescoes of St. Francis's life, the lives of other holy figures. The about spectacular image featuring the star and cross motif is in the painting of Francis over the altar, showing Francis enthroned in heaven with gold brocade wear and seated on an Islamic textile woven in golden brocade.

Basilica of San Francesco

The Meanings of Islamic Influence in the Basilica

Michael Calabria finds that Francis'south humble encounter with al-Kamil had a deep impact on the expression of his faith. Francis returned from Egypt and wrote a letter of the alphabet to the rulers, maxim that there should be a sound used to call worshippers to prayer—such bells come from the Franciscan tradition. He was impressed with the participation of all in the five daily Islamic prayers, and with the names of God. He wrote a prayer of supplication to God, unlike any other in the tradition of Christian sacred literature at that time. The final gesture of Francis's life was that he asked to be laid on the blank ground, mayhap a gesture of submission to God. These are very reminiscent of aspects of Islamic worship he would have witnessed during his fourth dimension in al-Kamil'south presence.

As for the Basilica, the magnificent structure contradicts Francis' message of poverty, but it is not so ironic that the Basilica has unconsciously peradventure, drawn elements from the Islamic society he visited into the realm of western Christendom. This arose, says Calabria, "not past trouncing or triumphing, or confronting or coercing, but in a seamless blending of styles arising simply from a mutual appreciation and sharing what is cute. In this fashion the Basilica tin be said to be a fitting reflection of what occurred in Francis' own personal encounter with Islam, inspiring his ain religion and prayer." What was created, he said, is a common visual language across cultural and religious boundaries. This mutual vision and language of beauty is too ofttimes forgotten a world that in more recent centuries has accepted rigid dichotomies of east and west, European and African, European and Asian, Christian and Muslim, to the exclusion of a deeper and more than integral unity."

Text and paradigm sources: Calabria, Michael D. "Seeing Stars: Islamic Decorative Motifs in the Basilica of St. Francis." Select Proceedings from the First International Conference on Franciscan Studies: The World of St. Francis of Assisi, Siena, Italy, July sixteen-20, 2015. Pp. 63-72; also, lecture at Georgetown Academy by Fr. Michael Calabria, "The Confluence of Cultures: Italo-Islamic Art and the Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi" (View video lecture at the Center for Contemporary Arab Studies at Georgetown Academy, August 2014, at http://vimeo.com/226482289).

Other images of the Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Basilica_di_San_Francesco_(Assisi), Roberto Ferrari from Campogalliano (Modena), Italy under Wikimedia commons; upper & lower churches: Basilica of St. Francis by Berthold Werner (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Eatables.

Mathematical and Scientific Exchanges

Mathematics is office of merchandise for at to the lowest degree three reasons: (i) Information technology is needed in navigation on the seas, along with astronomy. (2) Merchants need to keep records of goods and money, especially when their routes encompass many lands, and when they finance their journeys with other people'south money—such as families, trade agreements, or lenders. For that, they need bookkeeping, or bookkeeping. (3) Another important use of mathematics is in building and engineering. When trade grows, people want to build roads, walls to defend their cities, and fine buildings to prove off their wealth. Mathematics was also a source of intellectual pride, every bit rulers and scholars matched wits to solve mathematical problems, out of curiosity or the want to discover new truths. During the flow of the Crusades and later on—especially during the twelfth century and across, mathematical knowledge from Islamic lands entered Europe through translations, forth with many other kinds of scientific and technical cognition. Every bit you may know, 1 of those innovations was the use of Hindi-Arabic numerals. Read about mathematician Fibonacci who helped introduce those numerals for all of the purposes higher up.

Fibonacci in Northward Africa and His Volume Liber Abaci

Europeans did not gain admission to the mathematical cognition found in Spain and Northward Africa until the 12th and 13th centuries. It entered Europe both through a translation of Farsi mathematician al-Khwarizmi's book on Algebra done in Kingdom of spain in the 12th century, and through Italy's North African connections and trade.

Fibonacci

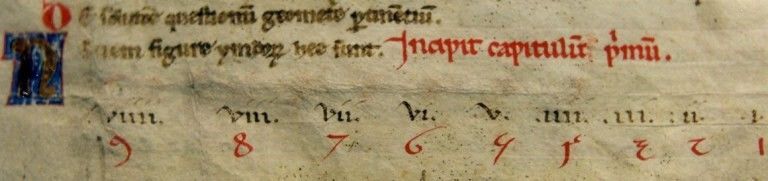

Leonardo of Pisa, who died in 1250, is better known equally Fibonacci. Leonardo'due south father took him as a kid to Algeria where he did concern in the Italian merchant community. He studied mathematics with a "marvelous" Muslim tutor, every bit he remembered. In 1202 he shared what he had learned of the mathematics used in Muslim lands with his book Liber Abaci—The Book of the Abacus. Liber Abaci introduced Hindi-Arabic numerals to Europeans. It became popular and enormously simplified business accounting and merchandise when they replaced Roman numerals. He, and the translator of al-Khwarizmi also introduced the concept of zero—the identify holder that allows writing any possible number using merely nine digits and nix. He explained how to summate using the numerals, how to write fractions and He goes to great lengths to describe how to practice arithmetic with these numerals, and how to use fractions and ratios. Leonardo of Pisa became famous, and introduced him to Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Ii—the same person with whom al-Kamil negotiated the treaty on Jerusalem. Frederick Two, who also corresponded with al-Kamil about mathematics, supported Fibonacci later in his life, and helped publish many books on mathematical ideas. was renowned for his thirst for noesis. In the 15th century, the printing printing spread Hindu–Standard arabic number system throughout Europe and beyond.

Prototype credits: "Roots: Legacy of Fibonacci," 1228 edition of Liber Abaci and image of Fibonacci at Emma Bell, Chalkdust: a Magazine for the Mathematically Curious, http://chalkdustmagazine.com/features/roots-legacy-of-fibonacci/.

To learn about many other contributions in mathematics, scientific discipline, applied science and the arts, visit http://islamicspain.idiot box/Arts-and-Science/The-Civilisation-of-Al-Andalus/index.html.

Culinary and Agricultural Exchanges from the Crusades

Saccharide

Like all plants, the saccharide cane found is a grass that articles sugar from sunlight and h2o. The juice in the stalk is very sweet. People liked its gustatory modality and started growing it thousands of years ago in Southeast Asia. Over the centuries, people brought the knowledge of how to grow sugarcane to India, and so to Persia and across medieval Muslim lands to Spain. Muslim traders and migrating farmers brought sugar to the Mediterranean lands, including the Iberian Peninsula, around thou. Europeans became aware of the sweet treat through visits to Muslim Espana, and through the luxury trade across the Mediterranean, carried on mainly by Italian merchants. Sugar was a rare luxury accessible only to the rich.

Crusaders who conquered what became the Latin Crusader States found sugar already being cultivated and refined. They learned these techniques from the Arabs and connected its cultivation, with the main center of the industry in Tyre in Lebanon. They likewise learned to use it in pastries made with fine wheat flour, fruit preservation, and candies, the name coming from the Standard arabic word qandi. The carbohydrate that Europeans enjoyed during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries came from the Crusader lands in the East.

Spices

Other items that Europeans learned of during the Crusades, and so began to import in greater amounts were spices and herbs. The near important was balm (Melissa officinalis), used in church services. Others were cinnamon, pepper, cloves, cardamom, cumin and various Mediterranean herbs such as oregano and sage, which were used in cooking. A merchant's guide from Florence of 1310–1340 lists 288 "Spices," which included "seasonings, perfumes, dyestuffs and medicinal of Oriental and African origin." Among the long list are chemicals used in coloring material and preserving nutrient, such equally alum, wax, gallnuts, and indigo, dyes for making bluish, red, yellow, and blackness fish gum, glue Arabic, soda ash, and many other things. Among the spices we think of equally seasonings, they imported citron, fennel, pepper, poppies, sumac, cloves, cinnamon, caraway, cardamom, ginger, mace (nutmeg) cumin, myrrh, frankincense, sandalwood, and rose water, to name merely a few.

Rice was first grown in tropical Southeast Asia, where information technology spread to Communist china and beyond in the east, and India and Persia, and Republic of iraq before reaching Mediterranean lands with irrigation systems that would allow it to abound. Rice was non at all common in Europe'southward common cold climate, only was a rare import. It was listed in the aforementioned merchant'south guide, as a "spice" which seems to have meant something rare and tasty.

Source of text: Wright, Clifford A. A Mediterranean Feast: <> Story of the Nascence of the Historic Cuisines of the Mediterranean, from the Merchants of Venice to the Barbary Crosaird, (Morrow, 1999), http://www.cliffordawright.com/caw/food/entries/display.php/topic_id/23/id/99/. ; Robert Due south. Lopez and Irving Westward. Raymond, translators, Medieval Merchandise in the Mediterranean World: Illustrative Documents (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), pp. 108-114. Excerpts from volume on medieval trade documents (List of 88 "spices").

Macaroni and Pasta

a medieval handbook of health

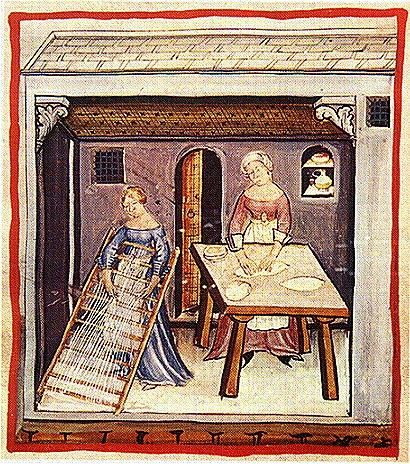

It may be hard to imagine Italian cooking without pasta, but the about mutual form of pasta dough entered Italy around the time of the Crusades. Durum wheat, or semolina, is a type of wheat that is low in wet, and can be stored for a long time for export. It has very high in gluten protein, which means that when made into dough, it is very stretchy—perfect for rolling into thin pasta sheets or made into many pasta shapes.

The history of pasta is very old, and was made from many types of grain. When the thin dough was dried, it was easy to shop, low-cal to pack for travels, and ready to eat after boiling in water a short time. It could be combined with any meat, sauce, or vegetable. It could even exist eaten sweetness, cooked with milk and beloved. There is a popular fable that Marco Polo learned of pasta in Cathay, simply it was in that location before he ever went, even though he surely learned about new types on his 13th century travels to Cathay. Durum wheat—semolina—was introduced to Europe through Muslim Espana, and the Crusaders were also exposed to information technology from the 11th century in Syria. Durum wheat itself probably originated in Central Asia, in today's Afghanistan, and spread beyond Muslim lands, like many other foods.

Source: http://www.katjaorlova.com/PastaClass.html. Image from the The Tacuinum Sanitatis, a medieval handbook of wellness, a translation and compilation from the Taqwīm as‑Sihhah (Maintenance of Health), an eleventh-century Arab medical treatise by Ibn Butlan of Baghdad. This is from a Vienna edition, showing pasta being rolled, cut and dried on a rack.

Source: https://www.sultanandthesaintfilm.com/education/cross-cultural-trade-cultural-exchange-crusades/

0 Response to "European Cultures Became Familiar With Islamic Art Through"

Postar um comentário